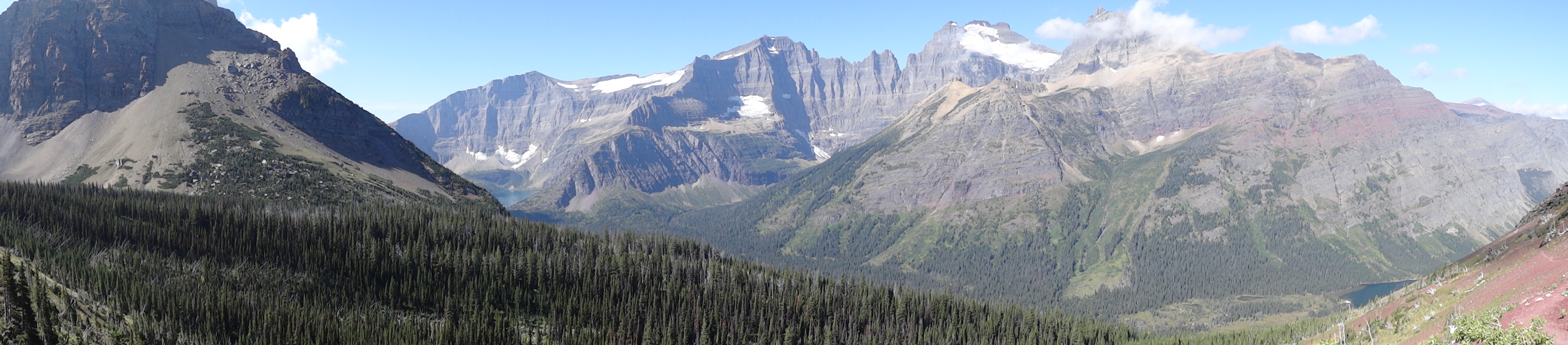

I am just over the crest of Swiftcurrent Pass, and it is very windy. In fact, it is clearly windy enough to blow a 150 pound man carrying a 35 pound backpack off of the trail and down the 1,000 foot cliff he is on. I decide it is a perfect place to stop for lunch.

I promised my wife that I would eat more on this trip, so I pick a little promontory off the trail and sit down beneath a ledge and slightly out of the wind. I lay rocks on top of my gear so it won’t blow away, and the re-hydrated granola with milk and blueberries is so good. I’m sitting there, eating this wonderful stuff that the wind is blowing out of my spoon before it reaches my mouth, literally on the edge of a most beautiful cliff, feeling this force that could care less whether it blows me over the side. A wonderful place and time.

You see a lot of mountain goats in Glacier, but they are almost always up in some incredibly inaccessible spot, so as I eat I am scanning the mountain across from me, looking for those improbably perched white spots. I finished my lunch without seeing anything on the other side, and as I stood up to get back on the trail I turned to face a goat sitting barely fifty feet away from me the whole time. I had not considered that I was myself in one of those incredibly inaccessible spots.

I love this about being outside, the unexpected miracle. Looking back now, on this trip and all the others, I think “that was not so hard.” You do these things, see and feel these things, and at that instant and forever after you know it is worth it. But there are moments of doubt, of weakened resolve. At the very start, I always feel deeply guilty for doing something so selfish. And the first day or two, surrounded by mountains and sky and wind, I sometimes wish I were home in a comfortable bed. But then I tell myself “this is where you are, now. You have to be somewhere, and you are here, so be here, now.” Then I am where I need to be.

I have always been very fortunate outdoors. I make good decisions. I prepare, I adapt. I allow myself briefly to credit marvels, and to be astonished at the simplest transactions of the physical world. I let go of the complacent conviction that the world has been made for humans by humans.

And then the trail is covered in bear shit. Sections of the trail above Cosley Lake, and later near Granite Park, had piles of bear shit every fifty feet. Those bears were eating a lot of berries, and if I was their medical professional I would recommend that they cut back after seeing this. At one point, I would say there was either a pack of 20 bears regularly shitting on this one trail, or one bear that really had an issue. I was so proud to come upon a pile of bear scat that looked totally different, fewer berries, intimations of hair and bone. Proud because I was able to see the difference, to see grizzly. Looking at shit.

You tell yourself “it is what it is” often, and realize that is perhaps both the most inane and the most profound statement, underlying all of life. The trail is steep, or it rains, or you cannot eat because you are too cold, but it is what it is, and you have to be somewhere, so this is it. And then you are standing at the top of Triple Divide Pass, feeling so tiny; or you are watching a bald eagle steal a trout from an osprey that has just swooped down to grab it from the mirror surface of a silent mountain lake; or you come upon a tiny glacial runoff, draped in perfect tiny moss, just beneath these enormous mountains, and you are so deeply, deeply content.

I was briefly worried that I would die, which does not happen to me often. Everyone has do die sometime, and I am 60 years old and ready, but please not just yet. You think “that was close; I have had enough.” You ask yourself if a view is worth risking your life. The Zen master intones “do not persist in bad decisions,” and I think perhaps to throw in my cards before I have lost everything. And then 24 hours later, after a hot shower and clean bed and two meals of meat and fat and beer, I begin to think “that was not so bad. If I just fix one or two little details, next time I will not have these problems.”

My last day inside Glacier was not easy, and then it was. After I met my bear, after I knew I would not lose fingers and would make it out, I had only a few miles to my last campsite, at Granite Park, a half-mile beneath Granite Park Chalet, the precise site of two of the three 1967 grizzly attacks in the same night that revolutionized the way the Park Service manages the bear/human interface. I had avoided the Chalet and its day-hikers on my way in over a week ago; now on my way out I considered stopping there for water, perhaps a dry bunk. But the Chalet was already closed unexpectedly for the season when I arrived, and the crew there heli-lifting out supplies informed me that my campsite farther down was closed due to bear activity. They said they would escort me to a safe spot to camp near the Chalet once the helicopter had finished the last lift, but I decided to hike on out the last four miles to my car at the trailhead, down an easy trail I already knew, past the closed campsite.

I had avoided the Chalet and its day-hikers on my way in over a week ago; now on my way out I considered stopping there for water, perhaps a dry bunk. But the Chalet was already closed unexpectedly for the season when I arrived, and the crew there heli-lifting out supplies informed me that my campsite farther down was closed due to bear activity. They said they would escort me to a safe spot to camp near the Chalet once the helicopter had finished the last lift, but I decided to hike on out the last four miles to my car at the trailhead, down an easy trail I already knew, past the closed campsite.

You have to be somewhere. It is what it is. And some views are worth it.