No man is a hero to his valet

Mme Anne-Marie Bigot de Cornuel

We were working our way up the steep slog of Tejas Trail when I realized I was yammering away like one of those trail women who simply won’t shut up. Just this summer in Colorado I’d remarked to hiking buddies Rob and Ed how irritating it was to cross a group of three women hiking, and one of them talks non-stop. The other two occasionally mumble “uh-huh,” but that one . . . she just won’t stop talking, even to breathe. But suddenly, here I was, yammering away.

I’d had the chance to hike with brother Chris, less than half my age and new to backpacking, so as new backpackers tend to be he was stunned by the climb, comparing his cardiovascular status to mine. I’d done this climb many times, and it makes a big difference to know what’s ahead–otherwise, you think “this shit just goes on and on.” Plus, I was in front, so he couldn’t really see that I was just as blown as he was. But still, for some bizarre reason, I was talking and talking and talking. At the time, I just filed that away, thinking “that’s weird, I never talk this much.”

I usually backpack alone–I’m a quiet guy since learning to talk less and listen more, and hiking long distances alone gives me the opportunity to think out all those things bouncing around inside my head that I don’t say out loud. Even hiking with Rob (quiet) and Ed (stream of consciousness chatterbox), there’s not much talking until we stop for the day. Backpacking is a very selfish enterprise, but for some strange reason hiking with family I had history with was different. We eventually made it to that evening’s campsite and settled in for a cold night.

You shouldn’t buy a whole bunch of backpacking equipment until you’re sure you enjoy sore feet and not bathing and sleeping very poorly: it is an investment, plus it takes time to figure out what specific equipment works for you. I had a spare sleeping bag Chris could use, and I had just replaced my faithful tent with a much lighter and smaller one, so Chris could use my old one. I’d bought that old 2-person tent dreaming that someday I’d be hiking with my sons, but that didn’t work out.  My pack is quite small, and the old tent wouldn’t fit inside, so I’d always had to carry it strapped to the outside on top of the pack. A confirmed solo hiker now, I was really, really looking forward to hiking with this new smaller tent stuffed inside my pack instead of looming just behind my head. ”Faster, lighter, less” is the solo hiker mantra (actually, at my age, it’s more like “I walk slower and slower every year; maybe if I got rid of some stuff I wouldn’t hike so slow”).

My pack is quite small, and the old tent wouldn’t fit inside, so I’d always had to carry it strapped to the outside on top of the pack. A confirmed solo hiker now, I was really, really looking forward to hiking with this new smaller tent stuffed inside my pack instead of looming just behind my head. ”Faster, lighter, less” is the solo hiker mantra (actually, at my age, it’s more like “I walk slower and slower every year; maybe if I got rid of some stuff I wouldn’t hike so slow”).

Chris surprised me when we met up at the trailhead after our respective 8-hour drives–he had a new pack but had also purchased food and various smaller items. In fact, his pack was absolutely full of food and various smaller items, and as I laid out the tent and sleeping bag on the ground next to his pack I asked “and where are you going to put these?” There had been some pre-trip rule-making by that wife of mine, something like “and you will NOT carry his tent and sleeping bag for him,” to which I had said less and listened more but thought “he’s a grown-ass man, we’ll figure it out.”

Somehow, amazingly, Chris triaged his new acquisitions and got the sleeping bag in there. We were on our way, albeit with his tent once again strapped to the outside of my pack, looming just behind my head.

I’ve been to GMNP perhaps a dozen times, but this is the first time I’ve been in the desert mountains at this time of year. On the way up, we quickly noticed the dusting of snow covering Guadalupe Peak across the canyon from us, and started seeing snow next to our trail within an hour or so. That night’s campsite, Pine Top, was empty and snow free. I showed Chris how to set up my old tent, then set up mine, and then we forced food down our gullets. I dispensed my one piece of GMNP wisdom–“the sun goes down fast, and when it does it gets cold fast, and then there isn’t shit to do”–and he said he was just planning on crashing into that tent anyway, so we were good.

Perhaps some people sleep really well backpacking. I have made trips where I have occasionally slept well, sunset to sunrise–14 hours once–but they are the exception. I am not a “build a campfire” camper, or a “have a drink around the fire” camper. The sun goes down, it gets real cold, and I crawl inside and anticipate the next day’s miles. Chris is a big guy, somewhere over six feet, and it was comforting to hear him rolling around on his new air mattress–scrunch, scrunch, scrunch–inside my extra sleeping bag, unable to get comfortable. All night long. ”Welcome to backpacking, brother,” I thought.

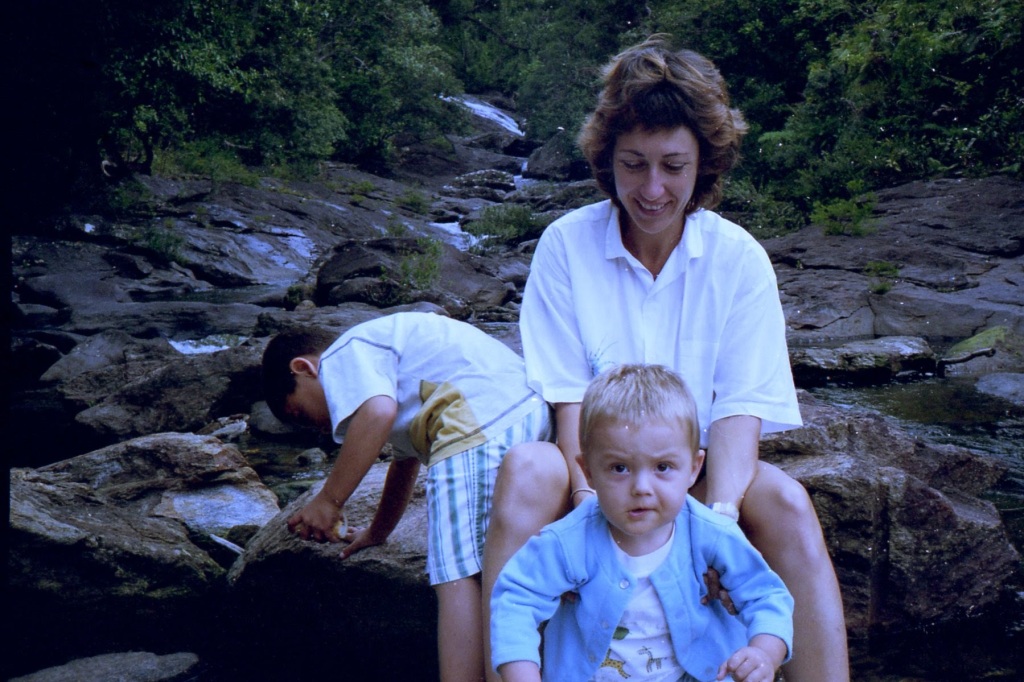

When he’s happy, Chris is like a giant but serious puppy. I did not know this about him, and it was fun. I missed a lot of his childhood, and our dad was a good man but too damn old to be a father again when Chris came around. I remember his mom once asking me during a brief visit back in the States to toss a ball with him in the yard, which I did without really understanding. I’d made it through my own childhood, and nobody’d tossed me a ball. Later, I had my own sons, and then I got it. And now he’s a young father with a clever wife and two awesome kids and a nice house and a serious career. That’s a lot, and you get to forget about all that backpacking. He was ready to get moving at sunup, ready for whatever the day would throw at him. I’d told him the day would be long but relatively easy, no big climbs until the last hour or so, when we’d also get some amazing views. So we took off, a counter-clockwise loop of the high country, and started hitting snow covering the trail within a few miles. Now, GMNP is not a heavily trafficked national park, and I’ve been moderately lost there in the past because sometimes the trail just disappears. But we pretty quickly were in 2-3 inches of snow, and a disappeared trail is unimaginably harder to find under snow.

Luckily for us, in the sections with the deepest snow, some solo hiker had already passed going the opposite direction, and it was reassuring to see someone else’s prints where I assumed the trail lay under the snow. I guessed it had been a ranger, because they were alone and didn’t seem to have ever stopped to pee or rest, and even though the prints were fresh and heading the opposite direction, we never saw the hiker. I did pause at one particularly vague stretch of trail to adjust my attitude. Chris asked “why are you stopping?” and I said “I just want to remember to use my own brain, and not rely completely on whoever left those prints; he might be lost.”

We finally made it to Bush Mountain, at just about the point where Chris was discreetly showing signs of doubting the justification my self-confidence. The amount of snow on the ground was impressive, and even though I know that section of park well enough to hike it without a map, I probably didn’t help by saying things like “even if the trail isn’t under this snow, we’re close to it because this is the only direction you can go.”

Pausing at the edge of Bush Mountain, overlooking the desert way below, Chris said he’d seen a large raptor sailing the updrafts, and a few minutes later I saw it close up as well. It had distinctive white patches on the undersides of its wings and was quite large. I was thrilled to research it later at home and learn that we had seen a juvenile golden eagle, which I have never seen anywhere in Texas. As distressing as our treatment of nature and the environment is, I regularly encounter something like this every year, some creature that hasn’t been seen for decades somewhere, but has suddenly returned.

Our last night, we had a permit to camp at the Bush Mountain campsite, perhaps a half-mile further down the trail from Bush Mountain itself. I would have preferred to camp our last night back at Pine Top, the site at the very top of the 4-mile trail leading up from the trailhead, but I’d worried the difficult extra two miles from Bush to Pine Top would make Chris’s last day hiking a death march and ruin it for him. The ranger who’d issued our permit had warned us before leaving that Bush “might be damp because of the recent snow,” but when we arrived it was entirely buried under several inches of snow. We took off our packs to think and snack while we surveyed all that snow, and soon enough a refreshed Chris surprised me by suggesting we just continue on to Pine Top. I really wasn’t looking forward to pitching tents in the snow, and especially to waking up in the middle of the night to pee and having to stumble around barefoot. I did take the unusual opportunity to boil some snow and drink a couple of cups of hydration; note to backpackers: do not boil snow to drink that you find under a pine tree. I will taste like pine and turpentine. But it was an experience.

I have an issue with authority figures, and even though I knew absolutely that we were the only people in the entire 86,000 acre backcountry, I was afraid of a ranger finding us camped at Pine Top instead of Bush Mountain, where we were supposed to be. Honestly, you do not want to give unnecessary opportunities for people in authority to use their authority, especially City, County, State, and Federal employees. I do not know what the fine is that a ranger could theoretically impose for not following the rules, but my general policy when out just being me is to stay off the radar and not be noticed.

The advantage in GMNP to camping at Pine Top your last night is that you can hike out before the sun comes up, get to your car, and drive back to Austin/Dallas before it’s dark again. I’d mentioned several times to Chris how cool doing that was, so he was anticipating it. What I had not anticipated is that it would begin raining lightly around 4 a.m., with heavy cloud cover blocking out the moonlight I’m accustomed to illuminating the trail when leaving pre-dawn. When I got up to check the sky, I could hear Chris rumbling around in his tent–scrunch, scrunch, scrunch–I don’t think he actually slept all night. In the dark he asked “is it raining? Should we go ahead on pack up?” I hate breaking camp in the rain; plus, I was pretty cozy in my sleeping bag, so I said “let’s give it half an hour.” But now I was awake, and he was still thrashing around next door, so after 15 minutes we broke camp and headed off in the dark in an almost imperceptible drizzle.

The way down is pretty easy, mostly because you compare it to coming up. You keep looking for lights on a trail across the canyon, some sign that someone other than you is in this enormous park, but you will not see anyone. When the desert sun comes up, it is always stupendous–I have never seen a boring desert sunrise. They tend to explode across the horizon, colors richer than you are accustomed to, more powerful than what you see elsewhere. I’m always aware of the irony of thinking you’re a rough and tough outdoorsman yet standing there stunned and unable to move, getting choked up and damp-eyed over a sunrise.

We had leisure to observe a lot of botany once the sun was up. Since becoming a homeowner, Chris has amazed everyone who knows him by his unsuspected passion for gardening. He and my wife can talk for hours–hours!–about lantana and vitex and salvia and a bunch of other words that mean only “plant” to me. We’d stopped at one point as he talked about various succulents he was seeing that he’d like to plant back home, and suddenly realized that all of the yucca plants had bloomed. You could turn 360 degrees and count hundreds of their stalks in the air completely surrounding you. It was amazing.

We got to the trailhead and our cars as people were arriving to set off up Guadalupe Peak on the other side of the canyon, the highest point in Texas and really the only backcountry in the park that gets visited much. It takes about 3 hours to get up the trail, which is very steep in places but well maintained, although I’d met a lady when I was getting my permit who told me it took her six hours to go up and four more to come down, so you are forewarned. Standing there dirty and I suppose “rugged” looking by our cars, a nice-looking woman approached us and asked for help using her Camelback; she said “you look like you know what you’re doing; I can’t get the water to come out,” and my brain couldn’t think of anything other to say than “suck harder,” but somehow the grownup inside me whispered “inappropriate.” She asked if we were just starting up, and her eyes got appropriately big when we said we’d just come down from two nights upcountry. Some women just know how to make a man feel manly. Anyway, I checked her Camelback and ultimately found that she was a little confused about the symbols on the valve for “open” vs. “closed.” ”Oops, blond moment,” she said with a wink and a smile, touching my arm, and there are men who would gladly hike a month for a reward at the end like that.

I realize now that hiking with Chris was like hiking with our father along, but better. I felt like I knew Chris better than I knew Dad, which is sort of weird, but that’s what it feels like. Chris is here, now. He looks like Dad, much more than I do. One of my sons as well looks so much like him. Perhaps it’s because I’m older now and feel how much it means to know a person. And the people we have, right there, right now, make all the difference.

, His dense brush like this

, His dense brush like this  , or His uncomfortably cold or wet places like this

, or His uncomfortably cold or wet places like this  or this

or this  .

. Then I looked around a bit and realized that this was just a melt-pond, and that Lake Elizabeth was up the snowy couloir at the far end.

Then I looked around a bit and realized that this was just a melt-pond, and that Lake Elizabeth was up the snowy couloir at the far end.